|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on an image to see a larger, more detailed picture.

|

|

|

|

|

| PROLOGUE: Roots of the Holocaust |

|

pg. 23 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

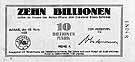

In the early 1920s, one dollar was worth 100 marks. In January 1923 the mark fell to 18,000 per dollar. Hyperinflation had replaced inflation. Later in the year, the exchange rate soared to 4.2 billion marks to the dollar. Before the spiral could be brought under control at the end of 1923, the hyperinflation had ruined millions of ordinary Germans who depended on wages, fixed incomes, or savings that had been carefully accumulated during better times. At the inflation's peak, a liter of milk or a loaf of bread could cost billions of marks. Prices changed not only daily but during the day as well. Currency held in the morning was worthless by nightfall.

|

As inflation rose, the Weimar government printed even more money. A ten-billion mark note, like the one pictured here, could buy practically nothing at the end of 1923.

As inflation rose, the Weimar government printed even more money. A ten-billion mark note, like the one pictured here, could buy practically nothing at the end of 1923.

Photo: Ullstein Bilderdienst

|

|

Hyperinflation benefited some financial manipulators who obtained huge bank loans, used them to buy businesses or property, and then were able to repay their loans with devalued currency. Most Germans, however, found themselves in dire economic straits, for it was not unusual for them to receive word from their banks indicating that their deposits no longer had any value.

|

This 1924 election poster urged Germans to vote for the German Nationalist People's Party (DNVP) and against the traitorous Democrats and Socialists.

This 1924 election poster urged Germans to vote for the German Nationalist People's Party (DNVP) and against the traitorous Democrats and Socialists.

Photo: Ullstein Bilderdienst

|

|

An early mecca for Germany's postwar nationalist movements, the region of Bavaria--and in particular Munich, its chief city--not only was affected by economic instability in 1923 but was also a place where plans to restore order by revolutionary means were under way. It is likely that such plans led to Hitler's meeting with the bespectacled Fritz Gerlich. Gerlich was no Nazi, but the two men shared interests, and they might have become allies. As it turned out, the opposite happened. Gerlich became one of Germany's most persistent and adamant opponents of Hitler and the Nazis. The origin of his loathing for Hitler is less than crystal clear, but it probably stemmed from assurances that Hitler gave Gerlich in the spring and then broke in the autumn of 1923. As Ron Rosenbaum documents the story in his 1998 book, Explaining Hitler, Gerlich backed the political aspirations of Gustav von Kahr, the right-wing nationalist governor of Bavaria. Hitler may have promised Gerlich that he, too, would support Kahr and not resort to illegal methods to advance the Nazi agenda. Subsequently, Gerlich witnessed the Munich Beer Hall Putsch on November 8-9, 1923, in which Hitler rashly attempted a takeover of the Bavarian state. The coup began on the evening of November 8, when Hitler and other Nazi Party leaders interrupted a patriotic meeting in Munich's Bürgerbräukeller, where Kahr was the featured speaker. With Nazi Storm Troopers surrounding the building, Hitler put Kahr under arrest and extorted his support at gunpoint.

|

|

|

|

|

|

1215: The Church's Fourth Lateran Council decrees that Jews be differentiated from others by their type of clothing to avoid intercourse between Jews and Christians. Jews are sometimes required to wear a badge; sometimes a pointed hat.

1215: The Church's Fourth Lateran Council decrees that Jews be differentiated from others by their type of clothing to avoid intercourse between Jews and Christians. Jews are sometimes required to wear a badge; sometimes a pointed hat.

|

1215: The Papacy sometimes protects Jews but makes it clear to one and all that the Jews are stateless beings who depend on the kindness of the Church for their very existence within Christendom.

1215: The Papacy sometimes protects Jews but makes it clear to one and all that the Jews are stateless beings who depend on the kindness of the Church for their very existence within Christendom.

|

1290: Jews are expelled from England. Hostility toward Jews will persist in the British Isles for the next 350 years, despite the absence of Jews until the mid-17th century.

1290: Jews are expelled from England. Hostility toward Jews will persist in the British Isles for the next 350 years, despite the absence of Jews until the mid-17th century.

|

1306: Philip IV orders all Jews expelled from France, with their property to be sold at public auction. Some 125,000 Jews are forced to leave.

1306: Philip IV orders all Jews expelled from France, with their property to be sold at public auction. Some 125,000 Jews are forced to leave.

|

Early 14th century: Gypsies establish themselves in Southeastern Europe.

Early 14th century: Gypsies establish themselves in Southeastern Europe.

|

|

|

|

|

| PROLOGUE: Roots of the Holocaust |

|

pg. 23 |

|

|

The Holocaust Chronicle

© 2009 Publications International, Ltd.

|

|